This site is best viewed with

a 4.0 browser and requires javascript |

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

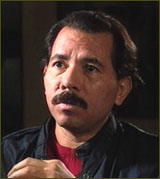

Daniel Ortega Saavedra was president of Nicaragua from 1985-1990. As one of the leading commanders of the Sandinista forces that ousted Nicaraguan dictator Anastasio Somoza in July 1979, he became head of the ruling junta in the subsequent leftist regime. In disputed elections in November 1984, he was elected president. During the 1980s Ortega led the Sandinistas in a long and bloody civil war against the U.S.-backed Contras -- a coalition of dissatisfied peasants, former Sandinista allies and Somozistas. A peace arrangement led to national elections in 1990, and Ortega and the Sandinistas were defeated by a right-centrist coalition led by Violeta Chamorro. Ortega relinquished the presidency in April 1991. He was interviewed for COLD WAR in September and October of 1997. This interview has been translated from Spanish. On the origins of the Sandinista revolution: We grew up in a situation where we didn't know what freedom or justice were, and therefore we didn't know what democracy was. ... The people of Nicaragua were suffering oppression. This made us develop an awareness which eventually led us to commit ourselves to the struggle against the domination of the capitalists of our country in collusion with the U.S. government, i.e. imperialism. And that's why our struggle took on an anti-imperialist character. One has to bear in mind that during my childhood and adolescence, I suffered the repression of the Somoza dictatorship in every way: economically, socially, as well as at the hands of the police -- because if we went out on the street to play baseball, for example, the police would come and beat us up and put us in prison. There was nowhere for young people to play sports, and all we experienced was repression. I also became aware through the experience of my family, because my father had fought alongside Sandino and had been imprisoned by Somoza, and my mother was also anti-Somoza and had been sent to jail. And they used to tell all those stories. On the other hand, there were no civic channels through which one might try to achieve change in our country, so we came to the conclusion that the only way to overthrow the dictatorship was through armed struggle. The Cuban Revolution hadn't triumphed yet. My idol was Sandino, and also Christ. I was brought up a Christian, but I regarded Christ as a rebel, a revolutionary, someone who had committed himself to the poor and the humble and never sided with the powerful. I had a Christian upbringing, so I would say that my main early influences were a combination of Christianity, which I saw as a spur to change, and Sandinism, represented by the resistance against the Yankee invasion. Later, the triumph of the Cuban Revolution was very influential, and Fidel, Che, and Camilo [Cienfuegos] became our main role models. There were also wars going on in Algeria and in Vietnam, which further encouraged us to believe that victory was possible. On Latin American support for the Sandinistas: [Cuba and Nicaragua] were close together and both suffered a dictatorship backed by the United States: there it was Batista, here it was Somoza. And there was a desire for profound change; I mean, not just replacing one dictatorship with another, or going from an iron dictatorship to a formal dictatorship within the framework of liberal politics: we wanted a more profound social change, a socialist change, and naturally that led us to identify with the Cuban Revolution. [Visiting Cuba], I really felt transported to a country that was challenging imperialism, that was putting forward an alternative to capitalism. I mean, it was challenging world capitalism and also the heavy weight of international imperialism. And one came face to face with these very spiritual, moral people who had a great fighting spirit. That's what I felt when I went to Cuba for the first time. ... Before the triumph of the Revolution, we received aid primarily from Cuba. Cuba had always supported the Sandinista struggle. Later on, as we developed the struggle in our country, Cuba was able to give us much more support. When the governments of Carlos Andres Perez in Venezuela, Omar Torrijos in Panama and Rodrigo Carazo in Costa Rica coincided in power, it became easier to bring in weapons from Havana through Panama, and then from Havana directly to Costa Rica, which of course assisted us greatly in overthrowing Somoza's dictatorship. [Weapons] arrived by air, on airplanes which transported the weapons to Panama. In Panama, the Cuban weapons would be added to some weapons that Panama and Venezuela were giving us, and then they were taken to Costa Rica. In Costa Rica, we would receive the weapons and bring them into the country clandestinely. I would say that that was the way the logistics worked. Most of the weapons were rifles, some artillery (especially antiaircraft artillery), some mortars, but above all it was rifles, which were what the population most needed, because people wanted to fight but they had no arms. ... Before that time, we received invaluable support from the late Costa Rican leader Jose Figueres, and his help was crucial for the first stage of our insurrection in October Ô77. During our preparations for the insurrection, we were able to count on some weapons which had been left over from Figueres's revolutionary struggle in the Forties; he gave us several dozen rifles, and some machine-guns (which I think included a .30-caliber one and a .50-caliber one). We also got some weapons from the United States, because some of our comrades worked in the solidarity [movement] in the United States and had connections there, so they found a way of buying weapons in the United States and bringing them to Nicaragua via Mexico. On the Sandinistas' relationship with the United States: [We took power] with great enthusiasm and a great desire to transform the country, but also with the worry that we would have to confront the United States, something which we regarded as inevitable. It's not that we fell into a kind of geopolitical fatalism with regard to the United States, but historically speaking the United States has been interfering in our country since the last century, and so we said, "The Yankees will inevitably interfere. If we try to become independent, the United States will intervene." I would say that we tried to neutralize that confrontation with the United States, and around September of Ô79 I went to the United Nations, and before that I visited Washington and had a meeting with President Carter. During the meeting with President Carter, we proposed the development of a new kind of relationship with the United States. During our exchange, [he said that] the American government was worried about the implications of the revolution and that the conservative sections of the United States perceived it as a threat. We insisted that this was an opportunity, as I said to Carter, for the United States to make good the historical damage they had inflicted on our country. Our national anthem still includes the words "Yankee, the enemy of humanity," and we said to him that the only way to abolish that line would be for the attitude of the imperialist powers to change throughout the world, and specifically towards Nicaragua. And then, in concrete terms, we asked President Carter for a certain amount of economic help, and for material support to build up a new army, because the old one had been wiped out. We needed weapons, because Nicaragua didn't manufacture any at the time, so we were asking them to help us in this respect. But they couldn't respond, because there was a public debate going on in the United States at that moment, and the conservatives were accusing Carter of opening the door to "communism," which was the word they used for these changes. It was up to the U.S. Congress to make these kinds of decisions, and the Congress did not want to approve such decisions. [Our relationship with Cuba] was precisely the challenge -- that the United States should respect our right to maintain friendly relations with whoever Nicaragua wanted. If the United States wanted to put conditions on Nicaragua's relations [with other countries], then it meant that we were starting off on the wrong foot, that the old imperialist attitude was still the same and there was nothing democratic about it at all, and that they were keeping up their dictatorial attitude throughout the world, supported by their economic and military power. So this meant that we started trying to find weapons in other parts of the world. Of course, the kind of support that Cuba could give us was very limited when it came to building up our army, since they didn't manufacture armaments in the quantities that we required. So we turned to Algeria and the Soviet Union for support. The first weapons that we received came from Algeria. Algeria identified very much with our struggle. We conducted a series of negotiations at the time, and the first reply we received came from Algeria. Then we began to receive support from other countries of the socialist community, and mainly from the Soviet Union. ... I remember perfectly well that when we began working in that direction, which we did quite openly, the U.S. government sent us an emissary, Mr. Thomas Enders, and I remember my conversation with him. He came to tell us very clearly that the United States was not going to allow a Soviet-Cuban communist bridgehead to be established in this continent. I said that we had a right to maintain relations with any other country, and that they should respect that right. And then he said that I should understand that they had to power to crush us, to which I replied that we were ready to fight and confront them even though they were a big power -- that Sandino had already confronted them in the past and that we were ready to do so again if they tried to crush us. On Soviet support for the Sandinista regime: Well, first of all, we did not assume that others would fight on our behalf; we the Nicaraguans were ready to fight ourselves. What we asked for were weapons so that we could defend ourselves -- that's what we asked of the Soviet Union, of the socialist countries of Eastern Europe, of the Algerians, of the Vietnamese; and that's what we received so that we could arm the Nicaraguan people and defend ourselves in that war imposed on us by Ronald Reagan's Administration over a number of years. [From the Soviet Union] we received rifles, which were still what our government most needed, because clearly, if the United States invaded us, we wouldn't be in a position to wage a mobile war with heavy armaments, so our defense would have to rely on our ability to develop popular resistance forces, guerrillas, throughout the country. So rifles were our main request, plus a few heavy armaments. Some tanks and helicopters arrived from the Soviet Union, but we never managed to get any MiG planes. We asked for planes so that we could use them in this war imposed on us by the United States, because with interceptor planes we could have neutralized the Contras' aerial logistics from Honduras, El Salvador and Costa Rica. But it seems that the United States put such heavy pressure on the Soviet Union, that even though the Soviets were willing and had already committed themselves in writing to send us MiG-21 planes and trained [our] pilots ... they began procrastinating. And I even remember that in one of the exchanges we had with them, they said that the United States had threatened [them] -- and I remember they even did it publicly during a visit to France, in the presence of President Mitterrand. We had explored the possibility of the French sending us Mirage [planes], and the French were willing; and when this became known, the Americans reacted by announcing publicly that they would not allow those armaments to enter Nicaragua and that they would bomb the Nicaraguan ports [if they arrived]. We asked the Soviets and the French to send the planes regardless, that we were willing to take the risk of Nicaragua being bombed. But in the end it wasn't possible for the planes to arrive in our country. There was an attempt, I remember, to send some smaller planes from Libya, and those planes got as far as Brazil, where they were intercepted and sent back to Libya. I think that the Soviet Union was guided by a socialist agenda, and that this socialist agenda was in the minds of the Soviet leadership and Party members. There was a conviction that the socialist cause was a just one, and so wherever there were struggles against colonialism, imperialism and neocolonialism, the Soviet Union would support those struggles and those causes, in the form of economic and military help. The economic assistance that the Soviet Union gave Nicaragua was invaluable. On the Sandinistas' war with the Contras: The fact is that the United States is behind what has happened in Nicaragua, and what they did was to promote a confrontation between Nicaraguans. And we already know how many millions of dollars and armaments they approved for the war in Nicaragua, and the things that were openly discussed in the U.S. Congress about our ports, the contempt of the United States for international law, for the resolutions of the United Nations Security Council and the decisions of the International Court of Justice, and so on. And of course, it was painful to have to accept that we were being confronted by another part of the Nicaraguan people, who were as poor as the Sandinistas who were defending the Revolution, but who acted as tools of an imperialist policy. ... This was a war that went beyond [Nicaragua], and without the United States the Contras would not have existed. Without the United States it would have been impossible for Somoza's former Guard to regroup, and it was they who started to organize the first counterrevolutionary units. Without the United States, there simply would not have been an armed uprising in our country. So I think it's very clear that external factors played a role in this matter, because I repeat, if I had had the resources to start fostering wars, I could have done so anywhere in the world -- in the United States, for example: first stir people up and then provide them with the weapons to defend the rights they feel they have been denied. ... I would say that what was going on here was a confrontation with the United States. That was their discourse and that's how they trained [the Contras]. I mean, they trained them to make the same speech to the people as Somoza had made. Somoza set himself up as dictator of our country in the name of anti-communism and the fight against communism, and according to Somoza, Sandino was a communist, as he was in the eyes of the United States. So the training they gave the Contras -- that whole manual the CIA prepared and all the rest of it -- was aimed at exacerbating an already backward mentality, because a population with more than 60 percent illiteracy is obviously a backward population; and a good part of the Contras themselves come from this same section of the population. On the Sandinistas' 1990 electoral defeat: [The United States] invaded Panama, which had a great influence on the elections in our country -- because this happened two months before the 1990 elections, and it broke up the support we had and the votes we had accumulated during the campaign. In December we had 47 percent support, with two months' campaigning still to do; [then] the invasion of Panama took place on December 23rd. And when we did a poll the following January, we had come down 10 points to 37 percent --- by which time we were one month away from the elections. ... It wasn't a completely free election because there was open interference from the United States, from President Bush, in the form of financial and political support to our opponents, as well as threats that the blockade would not be lifted and all the rest of it if [the anti-Sandinitsta opposition party] UNO didn't win. The decisive moment was the invasion of Panama. |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Fidel Castro | John Negroponte | Daniel Ortega Howard Hunt | Ana Guadalupe Martinez | Oscar Sobalvarro

|

||||||||||||||||||||