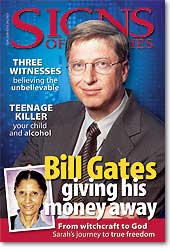

Bill Gates: Learning to Give

The richest man in the world”—the title has a certain ring to it. However, when referring to the current richest man in the world—Bill Gates—we’re speaking of an amount of money beyond normal comprehension.

Because most of his fortune is bound up in his 12.49 per cent share of Microsoft, the computer software company he founded, the figure is somewhat variable, dependant upon the current share price, but a recent estimate puts it at $US35 billion—that’s $US35,000,000,000—or somewhere about $A57 billion.

To acquire such a vast amount of money by age 47 requires earning at an extraordinary rate. Since 1986, when Microsoft was listed as a public company, Gates has made approximately $US65 per second, which works out at an hourly rate of some $US234,000, accumulating at that rate 24/7.

If Bill Gates were to keep his fortune in American $1 notes neatly stacked under his king-size mattress, he would need a parachute to get out of bed, freefalling about 9.6 kilometres the floor. Should he ever want to take all that cash with him on holidays, he would need 291 Boeing 747s.

In any currency, 35 billion is an enormous amount.

the Bill Gates/Microsoft story

William Henry Gates III was born and raised in a middle-class Seattle family, his father a lawyer and his mother a schoolteacher. His interest in computers began at age 13.

“In high school, there were periods when I was highly focused on writing software,” Gates recalls. “But for most of my high school years I had wide-ranging academic interests. My parents encouraged this, and I’m grateful that they did,” he says.

In 1973, Gates entered Harvard University, continuing his broad academic interest but not ignoring the fledgling personal computing world. Although he signed up for only one computer class during the whole time he was there, he continued working on his computer skills, developing a version of the programming language BASIC for the predecessor of today’s personal computers. In his third year at Harvard, Gates dropped out to concentrate on the company he had recently formed with childhood friend Paul Allen.

Reflecting on his incomplete college education, Gates urges the advantages of education. “My basic advice is simple and heartfelt,” he wrote in his New York Times column: “Get the best education you can. Take advantage of high school and college. Learn how to learn.

“It’s true that I dropped out of college to start Microsoft, but I was at Harvard for three years before dropping out—and I’d love to have the time to go back. As I’ve said, nobody should drop out of college unless they believe they face the opportunity of a lifetime. Even then, they should reconsider.”

However, Gates’s “opportunity of a lifetime” has grown into the world’s leading software company and into the world’s largest personal fortune. In 1980, the emerging Microsoft was engaged by computer manufacturer IBM to develop an operating system for their new personal computers. Microsoft delivered DOS. At that time, there were three competing operating systems available to personal computer users. DOS emerged as the dominant system.

In 1990, responding to the innovations of Apple, Microsoft released their Windows 3.0, with which their domination of the world’s computers was assured throughout the 1990s. Continuing their pattern of careful response to new technology—allowing time to learn from the mistakes and successes of competitors—Microsoft did not launch their assault of market-share in Internet software until 1996, but within just a few years, Microsoft was again in the number-one position as the world’s dominant supplier of web browsers.

the trials of Mr Microsoft

Behind each of these advances, Bill Gates has hovered as the larger-than-life personality of Microsoft. In 2000, he stepped out of the role of Microsoft’s CEO to focus more on software development and innovation. He continues to work in the roles of chairman and chief software architect.

As Microsoft’s alter ego, he is also often the target of many parties and protests questioning Microsoft’s business practices and corporate power—he has been another high-profile victim of the cream pie anti-globalisation protesters. Yet one of the most significant challenges to Microsoft has been an outgrowth of the incredible success and Microsoft’s aim to provide integrated computer packages.

In April 2000, Microsoft was found to have a monopoly situation in relation to its software sales and market dominance, where most new computers are forced to use Microsoft’s operating system, and their various software offerings are incompatible with competitors’ products. At the time of writing, legal proceedings are still under way—an example of the scrutiny to which Gates and the company he built is subject.

Describing Gates in Time magazine’s listing of the 100 most influential people of the 20th century, David Gelertner suggests Gates is neither as good nor as bad as the hype surrounding him suggests.

“Few living Americans have been so resented, envied and vilified,” writes Gelertner. “But in certain ways, his career is distinguished by decency—and he hasn’t got much credit for it. And yet we tend to overlook (in sizing him up) Gates’ basic decency.

“He has repeatedly been offered a starring role in the circus freak show of American Celebrity. . . . He has turned it down. He does not make a habit of going on TV to pontificate, free-associate or share his feelings. His wife and [three] young child[ren] are largely invisible to the public, which represents a deliberate decision.”

The corporate structure of Microsoft also allows a more democratic sharing of the profits among its more than 50,000 employees—perhaps reflecting Gates’s middle-class beginnings. “The idea that a successful corporation should enrich not merely its executives and big stockholders but also a fair number of ordinary line employees is (although not unique to Microsoft) potentially revolutionary.”

Gelertner neatly summarises Gates’s philosophy: “Wealth is good. Gates has created lots and has been willing to share.”

learning to give

That credo is shared by many involved in his more obviously charitable causes. In a recent interview, musician and humanitarian campaigner Bono, reflecting upon the progress of his various causes—including Third World debt relief, the AIDS epidemic and other issues of economic justice, particularly in developing countries—said bluntly of Gates, “No single person has done more.”

But the practicalities of giving millions—and even billions—of dollars are more complicated than it might appear. After initial forays into philanthropy—he donated the proceeds from his two books, The Road Ahead (1995) and Business @ The Speed of Thought (1999) to non-profit education organisations—Gates combined two smaller organisations to form the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation in 2000. With an endowment of approximately $US24 billion, it is the largest charitable organisation in the USA.

Writing that same year, Gates admitted a steep learning curve in finding the best way of giving. “Recently I’ve been getting an education in philanthropy,” he said. “My wife and I are trying to learn how to give money to charitable organisations in ways that will do the most good.

“Distributing money effectively to charity is not nearly as easy as you might think. Discipline and a strategy are essential. Until fairly recently, my plan was to wait until later in my career to begin extensive giving, to allow time for a lot of focus.

“But I’ve accelerated my philanthropic plans,” Gates continues. “Melinda and I are convinced that there are certain kinds of gifts—investments in the future—that are better made sooner than later.”

The Gateses’ benevolence has two primary objectives: health and education—and enabling access to the benefits technology can bring in both these fields, particularly in economically disadvantaged communities in America and the developing world.

“My philanthropy will focus on spreading the benefits more quickly,” says Gates. “As many people as possible should share in the remarkable advances in education, technology and medicine that many of us take for granted.”

An example of this focus is a $US100 million AIDS-prevention initiative launched by Gates in India in late 2002.

“HIV/AIDS is at a relatively low level in India, and experience shows that countries that act at an early stage can prevent the disease from becoming widespread,” says Gates. “The India AIDS initiative marks a long-term commitment by the foundation to support India’s efforts to contain further spread of the disease.

“India is uniquely positioned to not only address its own HIV/AIDS challenges and save millions of lives, but also help other developing countries with emerging epidemics. With some of the best research capabilities anywhere, India is poised to be a global leader in the development of new HIV prevention technologies.”

As similar initiatives across the world begin to make a difference, Gates borrows some of his philosophy of giving from Andrew Carnegie, an American philanthropist of the early 20th century.

“Carnegie believed that the wealthy are custodians of society’s resources and have a moral obligation to spend altruistically and wisely,” Gates reasons. “Willing wealth to charity isn’t enough. ‘The man who dies thus rich dies disgraced,’ Carnegie declared.”

On the journey to becoming the world’s richest man, Bill Gates has learned a valuable lesson: “I’m a steward of some of society’s resources, and take the responsibility seriously. It’s a privilege to be in this position.”

Sources: Time, www.microsoft.com/billgates, www.gatesfoundation.org, www.u2.com, The Guardian, www.quuxuum.org/~evan/bgnw.html, New York Times.

Rubber meets the road

A report in The New York Times (January 27, 2003) announced that the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation will give $US200 million in a series of grants to “identify critical questions about the leading causes of death in developing countries and to create an international competition to entice scientists to solve them.”

Bill Gates says the aim is to save the lives of the millions dying of such common diseases as malaria, tuberculosis and malnutrition, among others. Speaking at the Davos, Switzerland, World Economic Forum in early 2003, he said the existence of diseases in the developing world was stifling their development. He hoped the grants would shatter the scientific “complacency” surrounding these largely ignored diseases, and shift priorities away from research into “rich-world” diseases to those affecting the two-thirds of the world’s population living in poor countries.

Gates said his idea came from the success David Hilbert, a German mathematician who challenged his peers in 1900 to find solutions to 23 problems* during the course of the 20th century, which resulted in breakthrough research and contributed to the development of computers, the source of Gates’s wealth.

Gates hopes to “draw in a lot of talent that hasn’t been aware of what could make a difference in terms of world health.”

Among the challenges to be considered are:

- block the reactivation of tuberculosis

- protect children from life-threatening diarrhoea and respiratory infections

- find ways to deliver combinations of micronutrients to improve child nutrition, cognition and survival.

* Four were solved, 16 have relatively complete solutions, and three still remain unsolved.

Home - Archive - Topics - Podcast - Subscribe - Special Offers - About Signs - Contact Us - Links

|

|

|

Copyright © 2006 Seventh-day Adventist Church (SPD) Limited ACN 093 117 689