|

Continued in

Second Article

The Wonders of the Yellowstone

First Article

by Nathaniel P.

Langford

Scribner's Monthly - An

Illustrated magazine for the People; May 1871;

Conducted by J.G. Holland; Scribner & Co.; New York

| |

|

| |

I HAD indulged, for

several years, a great curiosity to see the wonders of

the upper valley of the Yellowstone. The stories told by

trappers and mountaineers of the natural phenomena of

that region were so strange and marvelous that, as long

ago as 1866, I first contemplated the possibility of

organizing an expedition for the express purpose of

exploring it. During the past year, meeting with several

gentlemen who expressed like curiosity, we determined to

make the journey in the months of August and September. |

The Yellowstone and

Columbia, the first flowing into the Missouri and the

last into the Pacific, divided from each other by the

Rocky Mountains, have their sources within a few miles

of each other. Both rise in the mountains which separate

Idaho from the new Territory of Wyoming, but the

headwaters of the Yellowstone are only accessible from

Montana. The mountains surrounding the basin from which

they flow are very lofty, covered with pines, and on the

southeastern side present to the traveler a precipitous

wall of rock, several thousand feet in height. This

barrier prevented Captain Reynolds from visiting the

headwaters of the Yellowstone while prosecuting an

expedition planned by the Government and placed under

his command, for the purpose of exploring that river, in

1859.

The source of the

Yellowstone is in a magnificent lake, nearly 9,000 feet

above the level of the ocean. In its course of 1,300

miles to the Missouri, it falls about 7,200 feet. Its

upper waters flow through deep canons and gorges, and

are broken by immense cataracts and fearful rapids,

presenting at various points some of the grandest

scenery on the continent. This country is entirely

volcanic, and abounds in boiling springs, mud volcanoes,

huge mountains of sulphur, and geysers more extensive

and numerous than those of Iceland.

Old mountaineers and

trappers are great romancers. I have met with many, but

never one who was not fond of practicing upon the

credulity of those who listened to his adventures.

Bridger, than whom perhaps no man has experienced more

of wild mountain life, has been so much in the habit of

embellishing his Indian adventures, that they are

received by all who know him with many grains of

allowance. This want of faith will account for the

skepticism with which the oft-repeated stories of the

wonders of the Upper Yellowstone were received by people

who had lived within one hundred and twenty miles of

them, and who at any time could have established their

verity by ten days' travel.

Our company, composed

of some of the officials and leading citizens of

Montana, felt that if the half was true, they would be

amply compensated for all the troubles and hazards of

the expedition. It was, nevertheless, a serious

undertaking, and as the time drew near for our

departure, several who had been foremost to join us,

upon the receipt of intelligence that a large party of

Indians had come into the Upper Yellowstone valley,

found excuse for their withdrawal in various emergent

occupations, so that when the day for our departure

arrived, our company was reduced in numbers to nine, and

consisted of the following-named gentlemen: General H.

D. Washburn, who served with distinction during the war

of the rebellion, and subsequently represented the

Clinton District of Indiana in the Congress of the

United States; Samuel T. Hauser, President of the First

National Bank of Helena; Cornelius Hedges, a leading

member of the bar of Montana; Hon. Truman C. Everts,

late United States Assessor for Montana; Walter

Trumbull, son of Senator Trumbull; Ben. Stickney, Jr.;

Warren C. Gillette; Jacob Smith, and the writer.

The preparation was

simple. Each man was supplied with a strong horse, well

equipped with California saddle, bridle, and cantinas. A

needle-gun, a belt filled with cartridges, a pair of

revolvers, a hunting-knife, added to the usual costume

of the mountains, completed the personal outfit of each

member of the expedition. When mounted and ready to

start, we resembled more a band of brigands than sober

men in search of natural wonders. Our provisions,

consisting of bacon, dried fruit, flour, &c., were

securely lashed to the backs of twelve bronchos, which

were placed in charge of a couple of packers. We also

employed two colored boys as cooks.

Major-General Hancock,

in favorable response to our application for a military

escort, had given orders for a company of cavalry to

accompany us, which we expected to join at Fort Ellis,

in the Gallatin Valley—a distance of one hundred and

twenty miles from Helena. We were none the less obliged

to Gen. Hancock for his prompt compliance with our

application for an escort, because of his own desire,

previously expressed, to learn something of the country

we explored which would be of service to him in the

disposition of the troops under his command, for

frontier defense ; and if the result of our explorations

in the least contributed to that end, we still remain

the debtor of that officer for his courtesy and

kindness, without which we might have failed altogether

in our undertaking.

Our ride to Fort Ellis, through a well-settled portion

of the Territory, was accomplished in four days. That

portion of the valleys of the Missouri and Gallatin

through which we passed, dotted with numerous ranches,

presented large fields of wheat, oats, potatoes, and

other evidences of thrift common in agricultural

districts. Large droves of cattle were feeding upon the

bunch grass which carpeted the valleys and foot-hills.

Even the mountains, so wild, solemn, and unsocial a few

years ago, seemed to be domesticated as they reared

their familiar summits in long and continuous succession

along the bordering uplands. At the three forks, where

the Jefferson, Madison, and Gallatin unite and form the

Missouri, a thriving agricultural community has sprung

up, which must eventually grow into a town of

considerable importance. Entering the magnificent valley

of the Gallatin at this point, our course up the river

lay through one of the finest agricultural regions on

the continent. The soil is remarkably fertile, and the

valley stretches away on either side, a distance of

twenty miles, to immense mountain ranges, which traverse

its entire length, enclosing a territory as large as one

of the larger New England States, every foot of which is

susceptible of the highest cultivation.

Our ride to Fort Ellis, through a well-settled portion

of the Territory, was accomplished in four days. That

portion of the valleys of the Missouri and Gallatin

through which we passed, dotted with numerous ranches,

presented large fields of wheat, oats, potatoes, and

other evidences of thrift common in agricultural

districts. Large droves of cattle were feeding upon the

bunch grass which carpeted the valleys and foot-hills.

Even the mountains, so wild, solemn, and unsocial a few

years ago, seemed to be domesticated as they reared

their familiar summits in long and continuous succession

along the bordering uplands. At the three forks, where

the Jefferson, Madison, and Gallatin unite and form the

Missouri, a thriving agricultural community has sprung

up, which must eventually grow into a town of

considerable importance. Entering the magnificent valley

of the Gallatin at this point, our course up the river

lay through one of the finest agricultural regions on

the continent. The soil is remarkably fertile, and the

valley stretches away on either side, a distance of

twenty miles, to immense mountain ranges, which traverse

its entire length, enclosing a territory as large as one

of the larger New England States, every foot of which is

susceptible of the highest cultivation.

Bozeman, a picturesque

village of seven hundred inhabitants, situated at the

foot of the Belt Range of mountains, is considered one

of the most important prospective business locations in

Montana. It is near the mouth of one of the few mountain

passes of the Territory deemed practicable for railroad

improvement. Its inhabitants are patiently awaiting the

time when the cars of the "Northern Pacific" shall

descend into their streets. The village is neatly built

of wood and brick. Its surroundings are magnificent. The

eye can distinctly trace the mountains by which it is

encircled, a distance of four hundred miles.

Fort Ellis, three miles

distant, is built upon a table of land elevated above

the valley, and which overlooks it for a great distance.

Our party was welcomed by Colonel Baker, the commandant,

and we pitched our tent near the post.

On the morning

succeeding our arrival we were informed that, owing to

the absence on duty of most of the soldiers, a fraction

of a company—five cavalrymen and a lieutenant in

command—were all that could be afforded for our escort;

but, realizing that a small body of white men can more

easily elude a band of Indians than can a large party,

and without hesitating to consider the possible defense

which we could make against a war party of hostile Sioux

with this limited number, we declared ourselves

satisfied, and took our departure for the terra

incognita as fully assured of a successful journey

as if our number had been multiplied by hundreds.

Our pack-horses were

brought up and their loads fastened to them with that

incredible rapidity and skill which is the result only

of life-long practice. The dexterity with which a

skillful packer will load and unload his horses is

remarkable. The rope is thrown around the body of the

animal and securely fastened in less time than it takes

to tell it. No matter what the character of the beast,

wild or tame, it is under the perfect control of its

master. The broncho is, however, a refractory customer.

He has many tricks, unknown to his well-trained brother

of the East. Bucking is a frequent vice, for which there

is small remedy; but, as was proved in a single instance

on the morning we left the fort, that horse must be more

expert than was any in our train who can foil an

experienced packer. Every leap of the enraged brute only

increased the tension of the cord which bound and

finally subdued him, and rendered him tractable.

Once under way, our

little company, now increased to nineteen, presented

quite a formidable appearance, as by dint of whip and

spur our steeds gayly wheeled across the plain towards

the mountains. After a tedious ride of several hours up

steep acclivities, over rocks, and through dark defiles,

we at length passed over the summit of the mountain

range, took a last look of the beautiful valley of the

Gallatin, and descended into a ravine coursed by the

waters of Trail Creek. Following this two days, we came

to the Yellowstone, up which we rode to the solitary

ranch of the brothers Boteler—the last abode of

civilized man in the direction of our travels. These

hardy mountaineers received and entertained us in hearty

mountain style—giving us the best of everything their

ranch afforded, together with a great deal of

information and advice about the country, which we

afterwards found to be invaluable. The Botelers belong

to that class of pioneers, of which there are many in

the new Territories, who are only satisfied when their

location and field of operations are a little in advance

of civilization — exposed to privation and danger—and

yet unite with these discomforts some advantages of

hunting, trapping, and fishing not enjoyed by men

contented to dwell in safety. Free-hearted, jolly

and

brave, living upon such means as the country afforded,

accustomed to roam for days and weeks in the mountains

in pursuit of game and furs, their experience renewed

our courage, and the descriptions which they gave us of

the wonders they had seen increased our curiosity. It

was not pleasant, however, to learn that twenty-five

lodges of Crows had gone up the valley a few days before

our arrival, or to be told by a trapper whom we met that

he had been robbed by them, and, in common parlance,

"been set on foot," by having his horse and provisions

stolen. and

brave, living upon such means as the country afforded,

accustomed to roam for days and weeks in the mountains

in pursuit of game and furs, their experience renewed

our courage, and the descriptions which they gave us of

the wonders they had seen increased our curiosity. It

was not pleasant, however, to learn that twenty-five

lodges of Crows had gone up the valley a few days before

our arrival, or to be told by a trapper whom we met that

he had been robbed by them, and, in common parlance,

"been set on foot," by having his horse and provisions

stolen.

In anticipation of

possible trouble from this source, we organized our

company, and elected Gen. H. D. Washburn,

Surveyor-General of Montana, commander. It was

understood that we should make but one march each

day—starting at 8 A.M., and camping at 3 P.M. This

obviated the necessity of unpacking and cooking a

dinner. At night the horses were to be carefully

picketed, a fire built beyond them, and two of the

company to keep guard until one o'clock; then to be

relieved by two others, who were to watch until

daylight. This divided the labor among fourteen, who

were to serve as picket-men twice each week.

These precautionary

measures being fully understood, we left Boteler's,

plunging at once into the vast unknown which lay before

us. Following the slight Indian trail, we traveled near

the bank of the river, amid the wildest imaginable

scenery of river, rock, and mountain. The foot-hills

were covered with verdure, which an autumnal sun had

sprinkled with maroon-colored tints, very delicate and

beautiful. The path was narrow, rocky, and uneven,

frequently leading over high hills, in ascent and

descent more or less abrupt and' difficult. The

increasing altitude of the route was more perceptible

than any over which we had ever traveled, and the river,

whenever visible, was a perfect mountain torrent.

While

descending a hill into one of the broad openings of the

valley, our attention was suddenly arrested by half a

dozen or more mounted Indians, who were riding down the

foot-hills on the opposite side of the river. Two of our

company, who had lingered behind, came up with the

information that they had seen several more making

observations from behind a small butte, from which they

fled in great haste on being discovered. They soon rode

down on the plateau to a point where their horses were

hobbled, and for a long time watched our party as it

continued its course of travel up the river. Our camp

was guarded that night with more than ordinary

vigilance. A hard rain-storm, which set in early in the

afternoon and continued through the night, may have

saved us from an attack by these prowlers. While

descending a hill into one of the broad openings of the

valley, our attention was suddenly arrested by half a

dozen or more mounted Indians, who were riding down the

foot-hills on the opposite side of the river. Two of our

company, who had lingered behind, came up with the

information that they had seen several more making

observations from behind a small butte, from which they

fled in great haste on being discovered. They soon rode

down on the plateau to a point where their horses were

hobbled, and for a long time watched our party as it

continued its course of travel up the river. Our camp

was guarded that night with more than ordinary

vigilance. A hard rain-storm, which set in early in the

afternoon and continued through the night, may have

saved us from an attack by these prowlers.

When we started the

next morning, Gen. Washburn detailed four of our company

to guard the pack train,- while he, with four others,

rode in advance to make the most practicable selection

of routes. Six miles above our camp we ascended the

.spur of a mountain, which came down boldly to the

river's edge. From its summit we had a beautiful view of

the valley stretched out before us—the river fringed

with cottonwood trees—the foot-hills covered with

luxuriant, many-tinted herbage, and over all the

snow-crowned summits of the mountains, many miles away,

but seemingly rising from the midst of the plateau at

our feet. Looking up the river, the valley opened

widely, and from the rock on which we stood was visible

the train of pack-horses, slowly winding their way along

the sinuous trail, which followed the inequalities of

the mountain-side. The whole formed a scene of great

interest. Pursuing our course a few miles farther, we

camped just below the lower cañon of the river. Our

hunters provided us with a sumptuous meal of antelope,

rabbit, duck, grouse, and trout.

The night was very

cold, the mercury standing at 40° when we broke camp, at

eight o'clock the next morning. We remained some time at

the lower cañon of the Yellowstone, which, as a single

isolated piece of scenery, is very beautiful. It is less

than a mile in length, and perhaps does not exceed 1,000

feet in depth. Its walls are vertical, and, seen from

the summit of the precipice, the river seems forced

through a narrow gorge, and is surging and boiling at a

fearful rate—the water breaking into millions of

prismatic drops against every projecting rock.

After traveling six miles over the mountains above the

cañon, we again descended into a broad and open valley,

skirted by a level upland for several miles. Here an

object met our attention which deserves more than a

casual notice. It was two parallel vertical walls of

rock, projecting from the side of a mountain to the

height of 125 feet, traversing the mountain from base to

summit, a distance of 1,500 feet. These walls were not

to exceed thirty feet in width, and their tops for the

whole length were crowned with a growth of pines. The

sides were as even as if they had been worked by line

and plumb—The whole space between, and on either side of

them, having been completely eroded and washed away. We

had seen many of the capricious works wrought by erosion

upon the friable rocks of Montana, but never before upon

so majestic a scale. Here an entire mountainside, by

wind and water, had been removed, leaving as the

evidences of their protracted toil these vertical

projections, which, but for their immensity, might as

readily be mistaken for works of art as of nature. Their

smooth sides, uniform width and height, and great

length, considered in connection with the causes which

had wrought their insulation, excited our wonder and

admiration. They were all the more curious because of

their dissimilarity to any other striking objects in

natural scenery that we had ever seen or heard of. In

future years, when the wonders of the Yellowstone are

incorporated into the family of fashionable resorts,

there will be few of its attractions surpassing in

interest this marvelous freak of the elements. For some

reason, best understood by himself, one of our

companions gave to these rocks the name of the "Devil's

Slide." The suggestion was unfortunate, as, with more

reason perhaps, but with no better taste, we frequently

had occasion to appropriate other portions of the person

of his Satanic Majesty, or of his dominion, in

signification of the varied marvels we met with. Some

little excuse may be found for this in the fact that the

old mountaineers and trappers who preceded us had been

peculiarly lavish in the use of the infernal vocabulary.

Every river and glen and mountain had suggested to their

imaginations some fancied resemblance to portions of a

region which their pious grandmothers had warned them to

avoid. It is common for them, when speaking of this

region, to designate portions of its physical features,

as "Fire Hole Prairie,” the "Devil's Glen,"—" Hell

Roaring River," &c. —and these names, from a remarkable

fitness of things, are not likely to be speedily

superseded by others less impressive. We camped at the

close of this day's travel near the southwestern corner

of Montana, at the mouth of Gardiner's River.

After traveling six miles over the mountains above the

cañon, we again descended into a broad and open valley,

skirted by a level upland for several miles. Here an

object met our attention which deserves more than a

casual notice. It was two parallel vertical walls of

rock, projecting from the side of a mountain to the

height of 125 feet, traversing the mountain from base to

summit, a distance of 1,500 feet. These walls were not

to exceed thirty feet in width, and their tops for the

whole length were crowned with a growth of pines. The

sides were as even as if they had been worked by line

and plumb—The whole space between, and on either side of

them, having been completely eroded and washed away. We

had seen many of the capricious works wrought by erosion

upon the friable rocks of Montana, but never before upon

so majestic a scale. Here an entire mountainside, by

wind and water, had been removed, leaving as the

evidences of their protracted toil these vertical

projections, which, but for their immensity, might as

readily be mistaken for works of art as of nature. Their

smooth sides, uniform width and height, and great

length, considered in connection with the causes which

had wrought their insulation, excited our wonder and

admiration. They were all the more curious because of

their dissimilarity to any other striking objects in

natural scenery that we had ever seen or heard of. In

future years, when the wonders of the Yellowstone are

incorporated into the family of fashionable resorts,

there will be few of its attractions surpassing in

interest this marvelous freak of the elements. For some

reason, best understood by himself, one of our

companions gave to these rocks the name of the "Devil's

Slide." The suggestion was unfortunate, as, with more

reason perhaps, but with no better taste, we frequently

had occasion to appropriate other portions of the person

of his Satanic Majesty, or of his dominion, in

signification of the varied marvels we met with. Some

little excuse may be found for this in the fact that the

old mountaineers and trappers who preceded us had been

peculiarly lavish in the use of the infernal vocabulary.

Every river and glen and mountain had suggested to their

imaginations some fancied resemblance to portions of a

region which their pious grandmothers had warned them to

avoid. It is common for them, when speaking of this

region, to designate portions of its physical features,

as "Fire Hole Prairie,” the "Devil's Glen,"—" Hell

Roaring River," &c. —and these names, from a remarkable

fitness of things, are not likely to be speedily

superseded by others less impressive. We camped at the

close of this day's travel near the southwestern corner

of Montana, at the mouth of Gardiner's River.

Crossing this stream the next morning, we passed over

several rocky ridges into a valley which, for a long

distance, was crowded with the spires of protruding

rocks, which gave it such a dismal aspect that we named

it "The Valley of Desolation." The trail was so rough

and mountainous that we were able to travel but six

miles before the usual hour for camping. Much of the

distance was through fallen timber, almost impassable by

the pack train. A mile before camping we discovered on

the trail the fresh tracks of unshod ponies, indicating

that a party of Indians had recently passed over it.

Lieutenant Doane, with one of our company, had left us

in the morning, and did not come into camp this evening.

One of our horses broke his lariat during the night and

galloped through the camp, rousing the sleepers, who

grasped their guns, supposing the Indians were really

upon them.

Crossing this stream the next morning, we passed over

several rocky ridges into a valley which, for a long

distance, was crowded with the spires of protruding

rocks, which gave it such a dismal aspect that we named

it "The Valley of Desolation." The trail was so rough

and mountainous that we were able to travel but six

miles before the usual hour for camping. Much of the

distance was through fallen timber, almost impassable by

the pack train. A mile before camping we discovered on

the trail the fresh tracks of unshod ponies, indicating

that a party of Indians had recently passed over it.

Lieutenant Doane, with one of our company, had left us

in the morning, and did not come into camp this evening.

One of our horses broke his lariat during the night and

galloped through the camp, rousing the sleepers, who

grasped their guns, supposing the Indians were really

upon them.

We started early the

next morning and soon struck the trail which had been

traveled the preceding day by Lieutenant Doane. It led

over a more practicable route than the one we left. The

marks made in the soil by the travais (lodge-poles) on

the side of the trail showed that it had been recently

traveled by a number of lodges of Indians,—and a little

colt, which we overtook soon after making the discovery,

convinced us that we were in their immediate vicinity.

Our party was separated, and if we had been attacked,

our pack-train, horses, and stores would have been an

easy conquest. Fortunately we were unmolested, and, when

again united, made a fresh resolusion to travel as much

in company as possible. All precautionary measures,

however, unless enforced by the sternest discipline, are

soon forgotten—and danger, until actually impending, is

seldom borne in mind. A day had scarcely passed when we

were as reckless as ever.

From the summit of a commanding range, which separated

the waters of Antelope and Tower Creeks, we descended

through a picturesque gorge, leading our horses to a

small stream flowing into the Yellowstone. Four miles of

travel, a great part of it down the precipitous slopes

of the mountain, brought us to the banks of Tower Creek,

and within the volcanic region, where the wonders were

supposed to commence. On the right of the trail our

attention was first attracted by a small hot sulphur

spring, a little below the boiling point in temperature.

Leaving the spring we ascended a high ridge, from which

the most noticeable feature, in. a landscape of great

extent and beauty, was Column Rock, stretching for two

miles along the eastern bank of the Yellowstone. At the

distance from which we saw it, we could compare it in

appearance to nothing but a section of the Giant's

Causeway. It was composed of successive pillars of

basalt overlying and under- lying a thick stratum of

cement and gravel resembling pudding-stone. In both

rows, the pillars, standing in close proximity, were

each about thirty feet high and from three to five feet

in diameter. This interesting object, more from the

novelty of its formation and its beautiful surroundings

of mountain and river scenery than anything grand or

impressive in its appearance, excited our attention,

until the gathering shades of evening reminded us of the

necessity of selecting a suitable camp. We descended the

declivity to the banks of Tower Creek, and camped on a

rocky terrace one mile distant from, and four hundred

feet above the Yellowstone.

From the summit of a commanding range, which separated

the waters of Antelope and Tower Creeks, we descended

through a picturesque gorge, leading our horses to a

small stream flowing into the Yellowstone. Four miles of

travel, a great part of it down the precipitous slopes

of the mountain, brought us to the banks of Tower Creek,

and within the volcanic region, where the wonders were

supposed to commence. On the right of the trail our

attention was first attracted by a small hot sulphur

spring, a little below the boiling point in temperature.

Leaving the spring we ascended a high ridge, from which

the most noticeable feature, in. a landscape of great

extent and beauty, was Column Rock, stretching for two

miles along the eastern bank of the Yellowstone. At the

distance from which we saw it, we could compare it in

appearance to nothing but a section of the Giant's

Causeway. It was composed of successive pillars of

basalt overlying and under- lying a thick stratum of

cement and gravel resembling pudding-stone. In both

rows, the pillars, standing in close proximity, were

each about thirty feet high and from three to five feet

in diameter. This interesting object, more from the

novelty of its formation and its beautiful surroundings

of mountain and river scenery than anything grand or

impressive in its appearance, excited our attention,

until the gathering shades of evening reminded us of the

necessity of selecting a suitable camp. We descended the

declivity to the banks of Tower Creek, and camped on a

rocky terrace one mile distant from, and four hundred

feet above the Yellowstone.

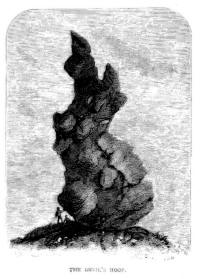

Tower Creek is a

mountain torrent flowing through a gorge about forty

yards wide. Just below our camp it falls perpendicularly

over an even ledge 112 feet, forming one of the most

beautiful cataracts in the world. For some distance

above the fall the stream is broken into a great number

of channels, each of which has worked a tortuous course

through a compact body of shale to the verge of the

precipice, where they re-unite and form the fall. The

countless shapes into which the shale has been wrought

by the action of the angry waters, add a feature of

great interest to the scene. Spires of solid shale,

capped with slate, beautifully rounded and polished,

faultless in symmetry, raise their tapering forms to the

height of from 80 to 150 feet, all over the plateau

above the cataract. Some resemble towers, others the

spires of churches, and others still shoot up as lithe

and slender as the minarets of a mosque. Some of the

loftiest of these formations, standing like sentinels

upon the very brink of the fall, are accessible to an

expert and adventurous climber. The position attained on

one of their narrow summits, amid the uproar of waters

and at a height of 250 feet above the boiling chasm, as

the writer can affirm, requires a steady head and strong

nerves yet the view which rewards the temerity of the

exploit is full of compensations. Below the fall the

stream descends in numerous rapids, with frightful

velocity, through a gloomy gorge, to its union with the

Yellowstone. Its bed is filled with enormous boulders,

against which the rushing waters break with great fury.

Many of the capricious formations wrought from the shale

excite merriment as well as wonder. Of this kind

especially was a huge mass sixty feel in height, which,

from its supposed resemblance to the proverbial foot of

his Satanic Majesty, we called the "Devil's Hoof." The

scenery of mountain, rock, and forest surrounding the

falls is very beautiful. Here, too, the hunter and

fisherman can indulge their tastes with the certainty of

ample reward. As a half-way resort to the greater

wonders still farther up the marvelous river, the

visitor of future years will find no more delightful

resting-place. No account of this beautiful fall has

ever been given by any of the former visitors to this

region. The name of "Tower Falls," which we gave it, was

suggested by some of the most conspicuous features of

the scenery.

Many of the capricious formations wrought from the shale

excite merriment as well as wonder. Of this kind

especially was a huge mass sixty feel in height, which,

from its supposed resemblance to the proverbial foot of

his Satanic Majesty, we called the "Devil's Hoof." The

scenery of mountain, rock, and forest surrounding the

falls is very beautiful. Here, too, the hunter and

fisherman can indulge their tastes with the certainty of

ample reward. As a half-way resort to the greater

wonders still farther up the marvelous river, the

visitor of future years will find no more delightful

resting-place. No account of this beautiful fall has

ever been given by any of the former visitors to this

region. The name of "Tower Falls," which we gave it, was

suggested by some of the most conspicuous features of

the scenery.

Early the next morning several of our company left in

advance, to explore a passage for our pack train over

the mountains, which were very steep and lofty. We had

been following a bend in the river,—but as no sign of a

change in its course was apparent, our object was, by

finding a shorter route across the country, to avoid

several days of toilsome travel. The advance party

ascended a lofty peak,—by barometrical measurement,

10,580 feet above ocean level,—which, in honor of our

commander, was called Mount Washburn. From its summit,

400 feet above the line of perpetual snow, we were able

to trace the course of the river to its source in

Yellowstone Lake. At the point where we crossed the line

of vegetation the snow covered the side of the apex of

the mountain to the depth of twenty feet, and seemed to

be as solid as the rocks upon which it rested.

Descending the mountain, we came upon the trail made by

the pack-train at its base, which we followed into camp

at the head of a small stream flowing into the

Yellowstone. Following the stream in the direction of

its mouth, at the distance of a mile below our camp, we

crossed an immense bed of volcanic ashes, thirty feet

deep, extending one hundred yards along both sides of

the creek. Less than a mile beyond, we suddenly came

upon a hideous-looking glen filled with the sulphurous

vapor emitted from six or eight boiling springs of great

size and activity. One of our company aptly compared it

to the entrance to the infernal regions, It looked like

nothing earthly we had ever seen, and the pungent fumes

which filled the atmosphere were not unaccompanied by a

disagreeable sense of possible suffocation. Entering the

basin cautiously, we found the entire surface of the

earth covered with the incrusted sinter thrown from the

springs. Jets of hot vapor were expelled through a

hundred natural orifices with which it was pierced, and

through every fracture made by- passing over it. The

springs themselves were as diabolical in appearance as

the witches' caldron in Macbeth, and needed but the

presence of Hecate and her weird band to realize that

horrible creation of poetic fancy. They were all in a

state of violent ebullition, throwing their liquid

contents to the height of three or four feet. The

largest had a basin twenty by forty feet in diameter.

Its greenish-yellow water was covered with bubbles,

which were constantly rising, bursting, and emitting

sulphurous gas from various parts of its surface. The

central spring seethed and bubbled like a boiling

caldron. Fearful volumes of vapor were constantly

escaping it. Near it was another, not so large, but more

infernal in appearance. Its contents, of the consistency

of paint, were in constant, noisy ebullition. A stick

thrust into it, on being withdrawn, was coated with

lead-colored slime a quarter of an inch in thickness.

Nothing flows from this spring. Seemingly, it is boiling

down. A fourth spring, which exhibited the same physical

features, was partly covered by an overhanging ledge of

rock. We tried to fathom it, but the bottom was beyond

the mach of the longest pole we could find. Rocks cast

into it increased the agitation of it’s waters. There

were several other springs in the group, smaller in

size, but presenting the same characteristics.

Early the next morning several of our company left in

advance, to explore a passage for our pack train over

the mountains, which were very steep and lofty. We had

been following a bend in the river,—but as no sign of a

change in its course was apparent, our object was, by

finding a shorter route across the country, to avoid

several days of toilsome travel. The advance party

ascended a lofty peak,—by barometrical measurement,

10,580 feet above ocean level,—which, in honor of our

commander, was called Mount Washburn. From its summit,

400 feet above the line of perpetual snow, we were able

to trace the course of the river to its source in

Yellowstone Lake. At the point where we crossed the line

of vegetation the snow covered the side of the apex of

the mountain to the depth of twenty feet, and seemed to

be as solid as the rocks upon which it rested.

Descending the mountain, we came upon the trail made by

the pack-train at its base, which we followed into camp

at the head of a small stream flowing into the

Yellowstone. Following the stream in the direction of

its mouth, at the distance of a mile below our camp, we

crossed an immense bed of volcanic ashes, thirty feet

deep, extending one hundred yards along both sides of

the creek. Less than a mile beyond, we suddenly came

upon a hideous-looking glen filled with the sulphurous

vapor emitted from six or eight boiling springs of great

size and activity. One of our company aptly compared it

to the entrance to the infernal regions, It looked like

nothing earthly we had ever seen, and the pungent fumes

which filled the atmosphere were not unaccompanied by a

disagreeable sense of possible suffocation. Entering the

basin cautiously, we found the entire surface of the

earth covered with the incrusted sinter thrown from the

springs. Jets of hot vapor were expelled through a

hundred natural orifices with which it was pierced, and

through every fracture made by- passing over it. The

springs themselves were as diabolical in appearance as

the witches' caldron in Macbeth, and needed but the

presence of Hecate and her weird band to realize that

horrible creation of poetic fancy. They were all in a

state of violent ebullition, throwing their liquid

contents to the height of three or four feet. The

largest had a basin twenty by forty feet in diameter.

Its greenish-yellow water was covered with bubbles,

which were constantly rising, bursting, and emitting

sulphurous gas from various parts of its surface. The

central spring seethed and bubbled like a boiling

caldron. Fearful volumes of vapor were constantly

escaping it. Near it was another, not so large, but more

infernal in appearance. Its contents, of the consistency

of paint, were in constant, noisy ebullition. A stick

thrust into it, on being withdrawn, was coated with

lead-colored slime a quarter of an inch in thickness.

Nothing flows from this spring. Seemingly, it is boiling

down. A fourth spring, which exhibited the same physical

features, was partly covered by an overhanging ledge of

rock. We tried to fathom it, but the bottom was beyond

the mach of the longest pole we could find. Rocks cast

into it increased the agitation of it’s waters. There

were several other springs in the group, smaller in

size, but presenting the same characteristics.

The approach to them was unsafe, the incrustation

surrounding them bending in many places beneath our

weight,—and from the fractures thus created would ooze a

sulphury slime of the consistency of mucilage. It was

with great difficulty that we obtained specimens from

the natural apertures with which the crust is filled,—a

feat which was accomplished by one only of our party,

who extended himself at full length upon that portion of

the incrustation which yielded the least, but which was

not sufficiently strong to bear his weight while in an

upright positions, and at imminent risk of sinking into

the infernal mixture, rolled over and over to the edge

of the opening, andwith the crust slowly bending and

sinking beneath him, hurriedly secured the coveted

prize.

The approach to them was unsafe, the incrustation

surrounding them bending in many places beneath our

weight,—and from the fractures thus created would ooze a

sulphury slime of the consistency of mucilage. It was

with great difficulty that we obtained specimens from

the natural apertures with which the crust is filled,—a

feat which was accomplished by one only of our party,

who extended himself at full length upon that portion of

the incrustation which yielded the least, but which was

not sufficiently strong to bear his weight while in an

upright positions, and at imminent risk of sinking into

the infernal mixture, rolled over and over to the edge

of the opening, andwith the crust slowly bending and

sinking beneath him, hurriedly secured the coveted

prize.

There was something so

revolting in the general appearance of the springs and

their surroundings—the foulness of the vapors, the

infernal contents, the treacherous incrustation, the

noisy ebullition, the general appearance of desolation,

and the seclusion and wildness of the locations—that

though awe-struck, we were not unreluctant to continue

our journey without making them a second visit. They

were probably never before seen by white man. The, name

of "Hell Broth Springs," which we gave them, fully

expressed our appreciation of their character.

Our journey the next

day still continued through a country until then

untraveled. Owing to the high lateral mountain spurs,

the numerous ravines, and the interminable patches of

fallen timber, we made very slow progress; but when the

hour for camping arrived we were greatly surprised to

find ourselves descending the mountain along the banks

of a beautiful stream in the immediate vicinity of the

Great Falls of the Yellowstone. This stream, which we

called Cascade Creek, is very rapid. Just before its

union with the river it passes through a gloomy gorge,

of abrupt descent, which on either side is filled with

continuous masses of obsidian that have been worn by the

water into many fantastic shapes and cavernous recesses.

This we named "The Devil's Den." Near the foot of the

gorge the creek breaks from fearful rapids into a

cascade of great beauty. The first fall of five feet is

immediately succeeded by another of fifteen, into a pool

as clear as amber, nestled beneath overarching rocks.

Here it lingers as if half reluctant to continue its

course, and then gracefully emerges from the grotto,

and, veiling the rocks down an abrupt descent of

eighty-four feet, passes rapidly on to the Yellowstone.

It received the name of "Crystal."

The Great Falls are at the head of one of the most

remarkable cañons in the world— a gorge through volcanic

rocks fifty miles long, and varying from one thousand to

nearly five thousand feet in depth. In its descent

through this wonderful chasm the river falls almost

three thousand feet. At one point, where the passage has

been worn through a mountain range, our hunters assured

us it was more than a vertical mile in depth, and the

river, broken into rapids and cascades, appeared no

wider than a ribbon. The brain reels as we gaze into

this profound and solemn solitude. We shrink from the

dizzy verge appalled, glad to feel the solid earth under

our feet, and venture no more, except with forms

extended, and faces barely protruding over the edge of

the precipice. The stillness is horrible. Down, down,

down, we see the river attenuated to a thread, tossing

its miniature waves, and dashing, with puny strength,

the massive walls which imprison it. All access to its

margin is denied, and the dark gray rocks hold it in

dismal shadow.

The Great Falls are at the head of one of the most

remarkable cañons in the world— a gorge through volcanic

rocks fifty miles long, and varying from one thousand to

nearly five thousand feet in depth. In its descent

through this wonderful chasm the river falls almost

three thousand feet. At one point, where the passage has

been worn through a mountain range, our hunters assured

us it was more than a vertical mile in depth, and the

river, broken into rapids and cascades, appeared no

wider than a ribbon. The brain reels as we gaze into

this profound and solemn solitude. We shrink from the

dizzy verge appalled, glad to feel the solid earth under

our feet, and venture no more, except with forms

extended, and faces barely protruding over the edge of

the precipice. The stillness is horrible. Down, down,

down, we see the river attenuated to a thread, tossing

its miniature waves, and dashing, with puny strength,

the massive walls which imprison it. All access to its

margin is denied, and the dark gray rocks hold it in

dismal shadow.

Even the voice of its

waters in their convulsive agony cannot be heard.

Uncheered by plant or shrub, obstructed with massive

boulders and by jutting points, it rushes madly on its

solitary course, deeper and deeper into the bowels of

the rocky firmament. The solemn grandeur of the scene

surpasses description. It must be seen to be felt. The

sense of danger with which it impresses you is harrowing

in the extreme. You feel the absence of sound, the

oppression of absolute silence. If you could only hear

that gurgling river, if you could see a living tree in

the depth beneath you, if a bird would fly past, if the

wind would move any object in the awful chasm, to break

for a moment the solemn silence that reigns there, it

would relieve that tension of the nerves which the scene

has excited, and you would rise from your prostrate

condition and thank God that he had permitted you to

gaze, unharmed, upon this majestic display of natural

architecture. As it is, sympathizing in spirit with the

deep gloom of the scene, you crawl from the dreadful

verge, scared lest the firm rock give way beneath and

precipitate you into the horrid gulf.

We had been told by

trappers and mountaineers that there were cataracts in

this vicinity a thousand feet high; but, if so, they

must be lower down the canon, in that portion of it

which, by our journey across the bend in the river, we

failed to see. We regretted, when too late, that we had

not made a fuller exploration—for by no other theory

than that there was a stupendous fall below us, or that

the river was broken by a continued succession of

cascades, could we account for a difference of nearly

3,000 feet in altitude between the head and the mouth of

the cañon. In that part of the cañon which we saw, the

inclination of the river was marked by frequent falls

fifteen and twenty feet in height, sufficient, if

continuous through it, to accomplish the entire descent.

The fearful descent

into this terrific cañon was as accomplished with great

difficulty by Messrs. Hauser and Stickney, at a point

about two miles below the falls. By trigonometrical

measurement they found the chasm at that point to be

1,190 feet deep. Their ascent from it was perilous, and

it was only by making good use of hands and feet, and

keeping the nerves braced to the utmost tensions, that

they were enabled to clamber up the precipitous rocks to

a safe landing-place. The effort seas successfully made,

but none others of the company were disposed to venture.

From a first view of

the cañon we followed the river to the falls. A grander

scene than the lower cataract of the Yellowstone was

never witnessed by mortal eyes. The volume seemed to be

adapted to all the harmonies of the surrounding scenery.

Had it been greater or smaller it would have been less

impressive. The river, from a width of two hundred feet

above the fall, is compressed by converging rocks to one

hundred and fifty feet, where it takes the plunge. The

shelf over which it falls is as level and even as a work

of art. The height, by actual line measurement, is a few

inches snore than 350 feet. It is a sheer, compact,

solid, perpendicular sheet, faultless in all the

elements of grandeur and picturesque beauties. The cañon

which commences at the upper fall, half a mile above

this cataract, is here a thousand feet in depth. Its

vertical sides rise gray and dark above the fall to

shelving summits, from which one can look down into the

boiling, spray-tilled chasm, enlivened with rainbows,

and glittering like a shower of diamonds. From a shelf

protruding over the stream, 500 feet below the top of

the cañon, and 180 above the verge of the cataract, a

member of our company, lying prone upon the rock, let

down a cord with a stone attached into the gulf, and

measured its profoundest depths. The life and sound of

the cataract, with its sparkling spray and fleecy foam,

contrasts strangely with the sombre stillness of the

cañon a mile below. There all was darkness, gloom, and

shadow; here all was vivacity, gayety, and delight. One

was the most unsocial, the other the most social scene

in nature. We could talk, and sing, and whoop, waking

the echoes with our mirth and laughter in presence of

the falls, but we could not thus profane the silence of

the cañon. Seen through the cañon below the falls, the

river for a mile or more is broken by rapids and

cascades of great variety and beauty.

Between the lower and

upper falls the cañon is two hundred to nearly four

hundred feet deep. The river runs over a level bed of

rock, and is undisturbed by rapids until near the verge

of the lower fall. The upper fall is entirely unlike the

other, but in its peculiar character equally

interesting. For some distance above it the river breaks

into frightful rapids. The stream is narrowed between

the rocks as it approaches the brink, and bounds with

impatient struggles for release, leaping through the

stony jaws, in a sheet of snow-white foam, over a

precipice nearly perpendicular, 115 feet high. Midway in

its descent the entire volume of water is carried, by

the sloping surface of an intervening ledge, twelve or

fifteen feet beyond the vertical base of the precipice,

gaining therefrom a novel and interesting feature. The

churning of the water upon the rocks reduces it to a

mass of foam and spray, through which all the colors of

the solar spectrum are reproduced in astonishing

profusion. What this cataract lacks in sublimity is more

than compensated by picturesqueness. The rocks which

overshadow it do not veil it from the open light. It is

up amid the pine foliage which crowns the adjacent

hills, the grand feature of a landscape unrivaled for

beauties of vegetations as well as of rock and glen. The

two confronting rocks, overhanging the verge at the

height of a hundred feet or more, could be readily

united by a bridge, from which some of the grandest

views of natural scenery in the world could be

obtained—while just in front of, and within reaching

distance of the arrowy water, from a table one-third of

the way below the brink of the fall, all its nearest

beauties and terrors may be caught at a glance.

We rambled around the

falls and cañon two days, and left them with the

unpleasant conviction that the greatest wonder of our

journey had been seen.

We indulged in a last and lingering glance at the falls

on the morning of the first day of Autumn. The sun shone

brightly, and the laughing waters of the upper fall were

filled with the glitter of rainbows and diamonds.

Nature, in the excess of her prodigality, had seemingly

determined that this last look should be the brightest,

for there was everything in the landscape, illuminated

by the rising sun, to invite a longer stay. Even the

dismal cañon, so dark and gray and still, reflected here

and there on its vertical surface patches of sunshine,

as much as to say, “See what I can do when I try."

Everything had “put a jocund humor on." Long vistas of

light broke through the pines which crowned the

contiguous mountains, and the snow-crowned peaks in the

distance glistened like crystal. Catching the spirit of

the scene, we laughed and sung, and whooped as we

rambled hurriedly from point to point, lingering only

when the final moment came to receive the very last

impression.

We indulged in a last and lingering glance at the falls

on the morning of the first day of Autumn. The sun shone

brightly, and the laughing waters of the upper fall were

filled with the glitter of rainbows and diamonds.

Nature, in the excess of her prodigality, had seemingly

determined that this last look should be the brightest,

for there was everything in the landscape, illuminated

by the rising sun, to invite a longer stay. Even the

dismal cañon, so dark and gray and still, reflected here

and there on its vertical surface patches of sunshine,

as much as to say, “See what I can do when I try."

Everything had “put a jocund humor on." Long vistas of

light broke through the pines which crowned the

contiguous mountains, and the snow-crowned peaks in the

distance glistened like crystal. Catching the spirit of

the scene, we laughed and sung, and whooped as we

rambled hurriedly from point to point, lingering only

when the final moment came to receive the very last

impression. At length we

turned our backs upon the scene, and wended our way

slowly up the river-bank along a beaten trail. The last

vestige of the rapids disappeared at the distance of

half a mile above the Upper Fall. The river, expanded to

the width of 400 feet, rolled peacefully between low

verdant banks. The water for some distance was of that

emerald hue which is so distinguishing a feature of

Niagara. The bottom was pebbly, and but for the

treacherous quicksands and crevices, of which it was

full, we could easily have forded the stream at any

point between the falls and our camping-place. We

crossed a little creek strongly impregnated with

alum,—and three miles beyond found ourselves in the

midst of volcanic wonders of great variety and

profusion. The region was filled with boiling springs

and craters. Two hills, each 300 feet high, and from a

quarter to half a mile across, had been formed wholly of

the sinter thrown from adjacent springs—lava, sulphur,

and reddish-brown clay. Hot streams of vapor were

pouring from crevices scattered over them. Their

surfaces answered in hollow intonations to every

footstep, and in several places yielded to the weight of

our horses. Steaming vapor rushed hissingly from the

fractures, and all around the natural vents large

quantities of sulphur in crystallized form, perfectly

pure, had been deposited. This could be readily gathered

with pick and shovel. A great many exhausted craters

dotted the hillside. One near the summit, still alive,

changed its hues like steel under the process of

tempering, to every kiss of the passing breeze. The

hottest vapors were active beneath the incrusted surface

everywhere. A thick leathern glove was no protection to

the hand exposed to them. Around these immense thermal

deposits, the country, for a great distance in all

directions, is filled with boiling springs, all

exhibiting separate characteristics.

The most conspicuous of

the cluster is a sulphur spring twelve by twenty feet in

diameter, encircled by a beautifully scolloped

sedimentary border, in which the water is thrown to a

height of from three to seven feet. The regular

formation of this border, and the perfect shading of the

scollops forming it, are among the most delicate and

wonderful freaks of nature's handiwork. They look like

an elaborate work of art. This spring is located at the

western base of Crater Hill, above described, and the

gentle slope around it for a distance of 300 feet is

covered to considerable depth with a mixture of sulphur

and brown lava. 'The moistened bed of a small channel,

leading from the spring down the slope, indicated that

it had recently overflowed.

A few rods north of

this spring, at the base of the hill, is a cavern whose

mouth is about seven feet in diameter, from which a

dense jet of sulphurous vapor explodes with a regular

report like a high-pressure engine. A little farther

along we came upon another boiling spring, seventy feet

long by forty wide, the water of which is dark and

muddy, and in unceasing agitation.

About a hundred yards

distant we discovered a boiling alum spring, surrounded

with beautiful crystals, from the border of which we

gathered a quantity of alum, nearly- pure, but slightly

impregnated with iron. The violent ebullition of the

water had undermined the surrounding surface in many

places, and for the distance of several feet from the

mar gin had so thoroughly saturated the incrustation

with its liquid contents, that it was unsafe to approach

the edge. As one of our company was unconcernedly

passing near the brink, the incrustation suddenly

sloughed off beneath his feet. A shout of alarm from his

comrades aroused him to a sense of his peril, and he

only avoided being plunged into the boiling mixture by

falling suddenly backward at full length upon the firm

portion of the crust, and rolling over to a place of

safety. His escape from a horrible death was most

marvellous, and in another instant he would have been

beyond all human aid. Our efforts to sound the depths of

this spring with a pole thirty-five feet in length were

fruitless.

Beyond this we entered

a basin covered with the ancient deposit of some extinct

crater, which contained about thirty springs of boiling

clay. These unsightly caldrons varied in size from two

to ten feet in diameter, their surfaces being from three

to eight feet below the level of the plain. The contents

of most of them were of the consistency of thick paint,

which they greatly resembled, some being yellow, others

pink, and others dark brown. This semi-fluid was boiling

at a fearful rate, much after the fashion of a

hasty-pudding in the last stages of completion. The

bubbles, often two feet in height, would explode with a

puff, emitting at each time a villainous smell of

sulphuretted vapor. Springs six and eight feet in

diameter, but four feet asunder, presented distinct

phenomenal characteristics. There was no connection

between them, above or below. The sediment varied in

color, and not unfrequently there would be an inequality

of five feet in their surfaces. Each, seemingly, was

supplied with a separate force. They were embraced

within a radius of 1,200 feet, which was covered with a

strong incrustation, the various vents in which emitted

streams of heated vapor. Our silver watches, and other

metallic articles, assumed a dark leaden hue. The

atmosphere was filled with sulphurous gases, and the

river opposite our camp was impregnated with the mineral

bases of adjacent springs. The valley through which we

had made our day's journey was level and beautiful,

spreading away to grassy foot-hills, which terminated in

a horizon of mountains.

We spent the next day

in examining the wonders surrounding us. At the base of

adjacent foothills we found three springs of boiling

mud, the largest of which, forty feet in diameter,

encircled by an elevated rim of solid tufa, resembles an

immense caldron. The seething, bubbling contents,

covered with steam, are five feet below the run. The

disgusting appearance of this spring is scarcely atoned

for by the wonder with which it fills the beholder. The

other two springs, much smaller, but presenting the same

general features, are located near a large sulphur

spring of milder temperature, but

too

hot for bathing. On the brow of an adjacent hillock,

amid the green pines, heated vapor issues in scorching

jets from several craters and fissures. Passing over the

hill, we struck a small stream of perfectly transparent

water flowing from a cavern, the roof of which tapers

back to the water, which is boiling furiously, at a

distance of twenty feet from the mouth, and is ejected

through it in uniform jets of great force. The sides and

entrance of the cavern are covered with soft green

sediment, which renders the rock on which it is

deposited as soft and pliable as putty. too

hot for bathing. On the brow of an adjacent hillock,

amid the green pines, heated vapor issues in scorching

jets from several craters and fissures. Passing over the

hill, we struck a small stream of perfectly transparent

water flowing from a cavern, the roof of which tapers

back to the water, which is boiling furiously, at a

distance of twenty feet from the mouth, and is ejected

through it in uniform jets of great force. The sides and

entrance of the cavern are covered with soft green

sediment, which renders the rock on which it is

deposited as soft and pliable as putty.

About two hundred yards

from this cave is a most singular phenomenon, which we

called the Muddy Geyser. It presents a funnel-shaped

orifice, in the midst of a basin one hundred and fifty

feet in diameter, with sloping sides of clay and sand.

The crater or orifice, at the surface, is thirty by

fifty feet in diameter. It tapers quite uniformly to the

depth of about thirty feet, where the water may be seen,

when the geyser is in repose, presenting a surface of

six or seven feet in breadth. The flow of this geyser is

regular every six hours. The water rises gradually,

commencing to boil when about half way to the surface,

and occasionally breaking forth in great violence. When

the crater is filled, it is expelled from it in a

splashing, scattered mass, ten or fifteen feet in

thickness, to the height of forty feet. The water is of

a dark lead color, and deposits the substance it holds

in solution in the form of miniature stalagmites upon

the sides and top of the crater. As this was the first

object which approached a geyser, we, naturally enough,

regarded it with intense curiosity. The deposit

contained in the water of this geyser comprises about

one-fifteenth of its bulk, and an analysis of it, made

by Prof. Augustus Steitz, of Montana, gives the

following result :—Silica, 36.7; alumina, 52.4; oxide of

iron, 1.8 ; oxide of calcium, 3.2 ; oxide of magnesia,

1.8 ; soda and potassa, 4.1= 100.

While returning by a

new route to our camp, dull, thundering sounds, which

General Washburn likened to frequent discharges of a

distant mortar, broke upon our ears. We followed their

direction, and found them to proceed from a mud volcano,

which occupied the slope of a small hill, embowered in a

grove of pines. Dense volumes of steam shot into the air

with each report, through a crater thirty feet in

diameter. The reports, though irregular, occurred as

often as every five seconds, and could be distinctly

heard half a mile. Each alternate report shook the

ground a distance of two hundred yards or more, and the

massive jets of vapor which accompanied them burst forth

like the smoke of burning gunpowder. It was impossible

to stand on the edge of that side of the crater opposite

the wind, and one of our party, Mr. Hedges, was rewarded

for his temerity in venturing too near the rim, by being

thrown by the force of the volume of steam violently

down the outer side of the crater. From hasty views,

afforded by occasional gusts of wind, we could see at a

depth of sixty feet the regurgitating contents.

This volcano, as is

evident from the freshness of the vegetation and the

particles of dried clay adhering to the topmost branches

of the trees surrounding it, is of very recent

formation. Probably it burst forth but a few months ago.

Its first explosion must have been terrible. We saw

limbs of trees 125 feet high encased in clay, and found

its scattered contents two hundred feet from it. We

closed this day's labor by a visit to several other

springs, so like those already described that they

require no special notice.

(Continued in

The Wonders of

the Yellowstone - Second Article)

stats: 8077 words

and 13 images

|